The sunlight rises in sprawling waves through the pellucid glass and peeks through the shutters in my room, painting a plaid light fixture on the silver carpet to the left of my bed. The appetizing scents of basil and garlic flavor the air. Life continues loudly outside of my homely apartment in Bloomfield, as I lay swallowed by my feathery white comforter, twisting my ankles and finding comfort in the snaps and pops. If I don’t start moving now, I’ll start to remember things I wish I could forget.

Hunger is nice to think about. It’s easy.

Five flavors are necessary for a proper charcuterie board. My favorite is savory. Savory, like thinly sliced semi-transparent strips of prosciutto, or a pesto made of basil and sun-dried tomatoes. An umami, tender, impassioned flavor. The taste of resolve weakened, at the quickening of adolescent lust. Curiosity. Oh, how I yearned to know what all grown women knew –to feel what my body primed me to feel… Is this really what I want?

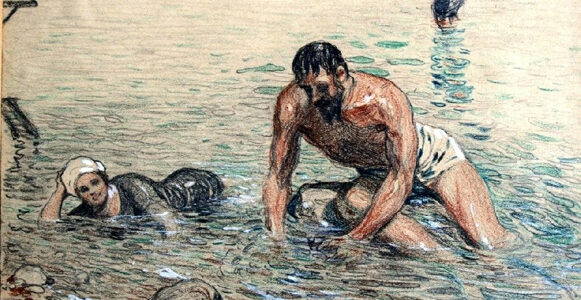

So on, there is salty. Think of the brine soaking pimento-stuffed olives. Think of the salt… from my perspiration. My eyes. Painfully squinting shut. Brackish tears sting as they roll down, down. Lubricating my dryness because I did not want to, and he was making me. It was supposed to be–

Creaminess that follows.

Creamy, like the smooth buttery goodness that melts into your mouth after a nibble of gouda cheese. Creamy, like the thick discharge that came out of me. Or maybe congealed is the right word. Something like cottage cheese. Was I not the only one?

I stayed while he used me, like a young girl does.

Acidity cuts through the curdle.

Visualize fermented pepperoni sausage, speckled with pockets of lard. Or the abrasive corrosion of lye-water inflicting itself upon freshly plucked olives. Taste the bitter tang of Kalamata olives on the tongue. Witness the pungent metal that flavors the air as I gasp for it. The bulging veins of my neck, rushing life into my brain – I can taste the blood. Why is he choking me? I am supposed to be his–

Sweetness that softens the blow. Sweet, like a butter-knife full of honey, rich and full. Or supple and crimson like a fresh raspberry speckled with seeds. This honeyed sap sweetens my lips. My cerebral oasis. Only tangible when reality is too cruel to bear.

Together these flavors are communion, plated neatly on a wooden platter.

The clicking chorus of locks unlatching on either side of my room rouse me from my daydreaming. Often, I remember what happened to me. I must continue anyway. Before my mind catches up with my body, I have already gravitated towards the commotion formulating around our laminate kitchen island. Seasoned grilled chicken sizzles on a skillet on the induction burner. Carly eyes the skillet intently while mixing bows of farfalle pasta into a maroon pesto sauce. Brenda and Gracen sit at the kitchen island, salivating over the delectable arrangement of meats and cheeses displayed before them on the charcuterie board. I draw closer and I see Zoe, back-to-back with Carly, grabbing a few strawberries dipped in cocoa. What is this for?” I say to everyone at once. I don’t listen for a reply; a realization strikes me: People that love each other don’t really need a reason to drink wine and eat together. I place myself beside my friends in front of the wooden charcuterie platter. We distract each other from our memories in this way. Like food itself, we sustain each other. I am often unsure of the love that I have had in the past.

I am sure that this love is real.

So, we all sit at the kitchen island, and drink wine, and we eat pesto pasta, and chocolate-covered strawberries and pepperoni and gouda cheese.

*

Angel Kermah is the literary and arts intern for Issue 13. She will graduate in May of 2026 from Montclair State University with a bachelor’s in Medical Humanities. Her creative nonfiction piece “Charcuterie Board” is her first publication in Narrative Northeast. Her poem, “The Flower by the Wall” appeared in The College. She is also a self-published writer; her newsletter Mahogany’s Murmurs can be found on the platform Substack. Her work ranges from reflective personal essays, intimate poetry, and speculative short fiction stories. Continue Reading

Angel Kermah is the literary and arts intern for Issue 13. She will graduate in May of 2026 from Montclair State University with a bachelor’s in Medical Humanities. Her creative nonfiction piece “Charcuterie Board” is her first publication in Narrative Northeast. Her poem, “The Flower by the Wall” appeared in The College. She is also a self-published writer; her newsletter Mahogany’s Murmurs can be found on the platform Substack. Her work ranges from reflective personal essays, intimate poetry, and speculative short fiction stories. Continue Reading

Nina Smilow is a writer of all genres. Her work can be found in Black Fox Literary Magazine, Porridge Magazine, Pacifica Literary Review, and Literary Mama. She is a graduate of Sarah Lawrence’s MFA and splits her time between Portland, OR and New York.

Nina Smilow is a writer of all genres. Her work can be found in Black Fox Literary Magazine, Porridge Magazine, Pacifica Literary Review, and Literary Mama. She is a graduate of Sarah Lawrence’s MFA and splits her time between Portland, OR and New York.

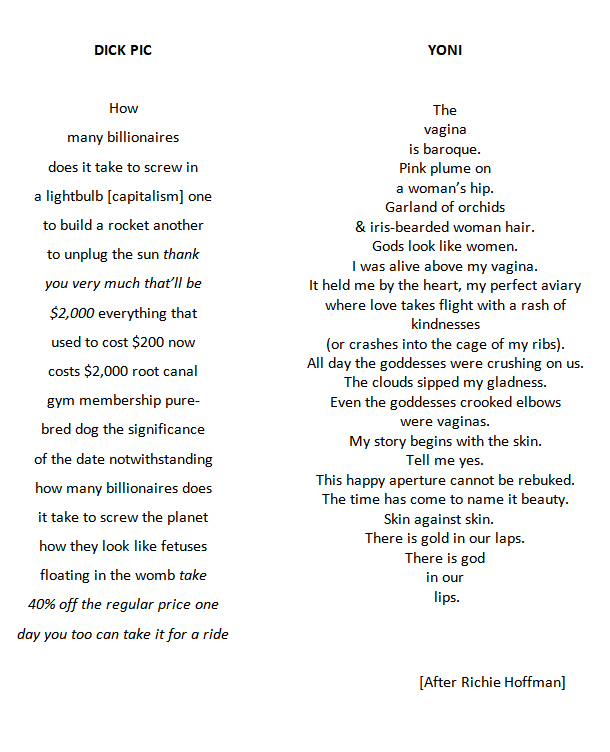

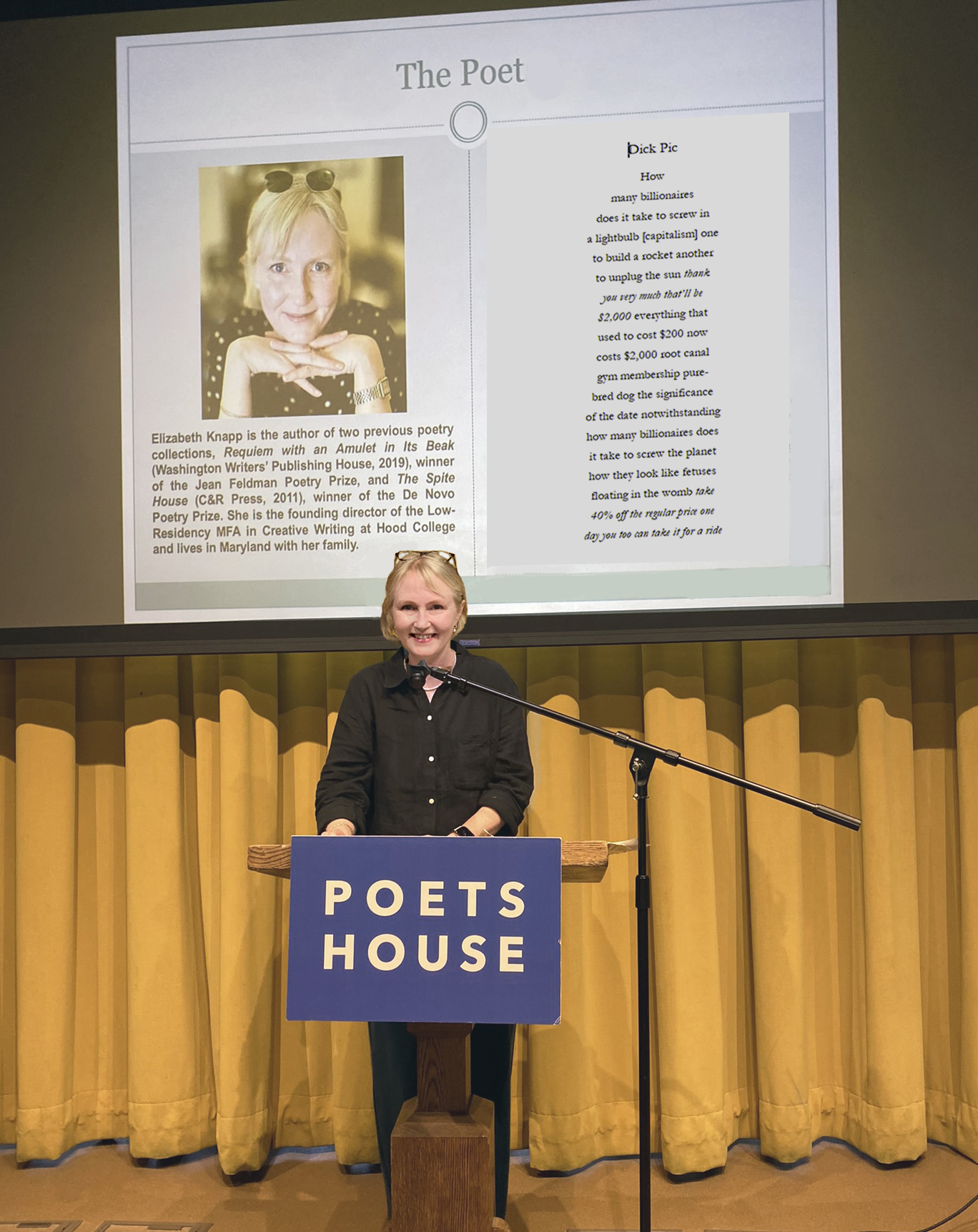

Pamela Hughes is the editor of Narrative Northeast. See the masthead for more info. During their dual book launch, Elizabeth & Pamela read from their poetry collections at Poets House in New York in September of 2025. Among other work, they read their poems, “Dic Pick” and “Yoni.” in tandem. “Dic Pick” was originally published in Causa Sui., while “Yoni” was first published in Hughes’ 2nd collection of poems, Femistry.

Pamela Hughes is the editor of Narrative Northeast. See the masthead for more info. During their dual book launch, Elizabeth & Pamela read from their poetry collections at Poets House in New York in September of 2025. Among other work, they read their poems, “Dic Pick” and “Yoni.” in tandem. “Dic Pick” was originally published in Causa Sui., while “Yoni” was first published in Hughes’ 2nd collection of poems, Femistry.

Isra Abdalla (she/her) is a second-year student pursuing an undergraduate degree in English Language and Literature. She is a Sudanese writer and a certified theatre kid (with a minor in theatre). Her work has been published in Partially Shy Magazine, Catheartic Magazine, Healthline Zine, and her university’s literary journal. More of her work can be found on

Isra Abdalla (she/her) is a second-year student pursuing an undergraduate degree in English Language and Literature. She is a Sudanese writer and a certified theatre kid (with a minor in theatre). Her work has been published in Partially Shy Magazine, Catheartic Magazine, Healthline Zine, and her university’s literary journal. More of her work can be found on

Tom Csanadi is retired pediatrician and is currently enrolled the Creative Writing certificate program through UC San Diego. As a first generation American of Hungarian refugee parents who fled their home country during the 1956 Revolution, he is passionate about drawing attention to the struggles faced by diverse groups of people. His view has also been honed from bearing witness to the full spectrum of the human condition during my career working with immigrant communities

Tom Csanadi is retired pediatrician and is currently enrolled the Creative Writing certificate program through UC San Diego. As a first generation American of Hungarian refugee parents who fled their home country during the 1956 Revolution, he is passionate about drawing attention to the struggles faced by diverse groups of people. His view has also been honed from bearing witness to the full spectrum of the human condition during my career working with immigrant communities

Paul Genega has published six full-length collections, including Outtakes: New and Selected Poems from Salmon Poetry in 2023. His work has appeared most recently in This Broken Shore and Orbis (UK). His honors include a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts and the “Discovery” Award.

Paul Genega has published six full-length collections, including Outtakes: New and Selected Poems from Salmon Poetry in 2023. His work has appeared most recently in This Broken Shore and Orbis (UK). His honors include a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts and the “Discovery” Award.

Shontay Luna is a poet / fanfiction author whose first job was a Movie Theater Concessionaire. Her poems have appeared in Olney Magazine, [alternate route] and The Literary Nest, among others. The author of four chapbooks, she lives in Chicago with her notebooks, pens and fanfiction fantasies.

Shontay Luna is a poet / fanfiction author whose first job was a Movie Theater Concessionaire. Her poems have appeared in Olney Magazine, [alternate route] and The Literary Nest, among others. The author of four chapbooks, she lives in Chicago with her notebooks, pens and fanfiction fantasies.