You have always trusted the forest. Here, danger could be seen and is known. The floor of the forest is layered with cool leaves that can be used to cover up faces. You’re lying here, laughing and out of breath; your brothers are lying beside you. The first one to move will be tickled by the rest, who will pretend to be monsters and fake-growl with the hunger of thin ghosts. All of you watch for the glint of teeth and the dazzling coils of predators.

The dense brush holds tigers, snakes, and water in a tiny creek that tastes fresh after the rain – your youngest brother knows the best places. The edge of the pretend forest, a neglected city garden, is where you and your brothers purchase time by tickling each other, or running and scrambling over rocks. As if the four of you never had to work. As if your father never accepted a packet of rupees and four quintals of wheat, one for each of you. As if he never told you when you were nine, Neela, go. As if he didn’t stop you and your brothers, including the youngest one, age five, from holding onto your mother’s sari, from nearly tearing it off her body when they wouldn’t let go.

Your hands could be washed of the clay, of the hard coal, and every day, your fingers moved more quickly than the legs of men who carried finished pyramids, fresh bricks for the furnace up and down steps. In summer, you and your brothers first broke coal, then walked without bending, as you learned to do, into the brick kiln, cloth covering your mouths from the smoke, December was joy and coldness, the fumes of the kiln more bearable when you could pour water into your mouths, which was not so scarce then. And after working, you and your brothers knew that you could leap over everything jagged you saw. In seconds, you could place many yards between the intimation of a threat, its small or large rustle, and yourself. You could easily outrun strangers’ hands, and in December, rejoice at less heat. Walking outside, into the kiln and back, then sleeping on the ground of the shanty, was still better than working in the factory.

Early one morning, while coming back from bringing a vessel of water, you notice a pile of bright folded cotton cloths on the ground. Because of the weight you carry, you carefully make your way toward it, even though you want to run.

December. Your birthday.

Maybe a pavaday from home – a dream. But all three half-naked little boys, the brothers who’d once thrown stones at palaces with you, or come at you with sticks for swords, are sleeping on the ground near the shanty. The angles of their arms and necks are not right. It’s as if they tried to escape.

Still hoping they’re playing a game, you set down the water, and tickle them. You listen for breath, but hear nothing. You’ve understood the danger too late. Eyes burning now, you run. To the place that you know as the forest. You reach there, stumbling and unsteady, but are forced to stop because you can’t see anymore, and are afraid.

Once, when you and your brothers were caught trying to run away from the brick kiln, the debt master who’d bargained with your father, punished all of you with no water for a day. How light your body had felt then, how small, how free, as if you had traveled in some unseen way to your mother.

December is cool and mornings usually feel fresh, but not today. Your lungs are scorched. Not for another thirty years, or maybe a hundred, will the water and land be safe again, as pure and unpolluted as they were hours before. Before the air burned and became a hateful thing.

Eight-thousand years ago, children huddled with their mothers in cool caves. Those caves are hidden deep in a forest, miles from here, and would have been so much safer to settle in, than shanty towns around the factory in Bhopal city, than the insignificant, easily-penetrated houses of corrugated metal and scavenged plywood. The walls of those shacks are sheets of plastic with small holes to breathe, set at the height of small children who are unable to refrain from peeking out.

All three of your brothers, limber and clever little boys, were gifted at nosing out delectable refuse, edibles in the garbage. Even though they nicknamed you Neelagai—antelope–for your thin quick legs–when they pretended to hunt you, none of them could find you here.

Other hunters have found you at the edge of your forest: methyl isocyanate, fleet-footed mercury and Sevin, the most experienced killer creeping like ground brush.

You remember rope, being pulled up into the kiln, then told to walk on bricks with your light feet since you could walk without breaking them. Now instead of rope, it feels like snakes coiling around your chest. Or dense vines tightening at your throat.

Water. You need water for the burning thirst, the invisible thief of your air. Your chest hurts. You push out poison air, but breath in more.

The death toll among Bhopal’s shanty-town families is estimated by the number of shrouds that were ordered. Twenty-thousand is a paltry number for memorials, excluding families who didn’t have money for shrouds. Fathers who didn’t receive reparation for dead children. Fathers and older brothers were coughing too much to bargain, their eyes watering. After the burning, many eyes turned sightless. Corneas clouded; ulcers branching like thin cacti.

Cactus are plants that you’ll never travel to deserts to see. You and your brothers saw some once in a comic book you found in the garbage. A small man with red beard and a large hat, standing next to a cactus. Your youngest brother laughed and laughed when you tried to imitate that frowning man.

You die knowing about your brothers, but not about the numbers of the many dead.

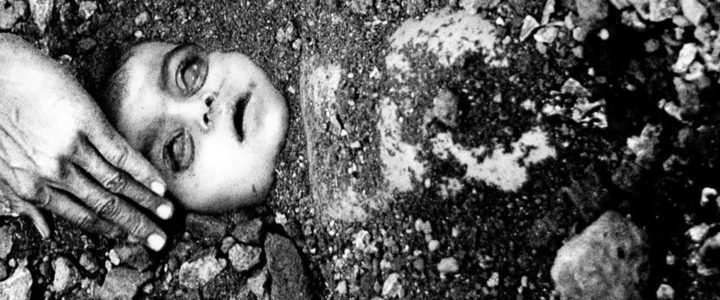

In death, you look like the image of a young girl, asleep after a bath, one of the emperor’s miniatures that was engraved hundreds of years ago by artisans so skilled that when they finished crafting monuments, Emperor Jahangir ordered them blinded.

The forest can be trusted to absorb you.

All this was caused by someone used to ordering something to be done somewhere else, the back of his head under a beam of light from a window that has been opened on a summer day, allowing the Houston air into the office for a few seconds while the air conditioning kicked in.

In flower pots near the entrance, some of them propped up by red bricks, there are bright-red small carnations, grown cheap in India with help from pesticides and fertilizers manufactured there, also for cheap, gotten with illegible signatures secured by government payments. In another corner, stands a Pac-Man arcade game of blinking lights and neon colors, more predators and prey. It is a game that you would have loved to look at, Neela, that you would have loved to play.

Chaya Bhuvaneswar is a practicing physician and writer whose work has appeared in Nimrod, Bangalore Review, Blue Lake Review and the Asian American Literary Review, and received a Henfield Transatlantic Writing Award as well as a Glimmer Train Honorable Mention and scholarship to Squaw Valley. She is at work on a novel and lives in the US with her family.

Chaya Bhuvaneswar is a practicing physician and writer whose work has appeared in Nimrod, Bangalore Review, Blue Lake Review and the Asian American Literary Review, and received a Henfield Transatlantic Writing Award as well as a Glimmer Train Honorable Mention and scholarship to Squaw Valley. She is at work on a novel and lives in the US with her family.

Related Posts

« RIB-CAGED BIRD – Laura Coe Moore THREE P0EMS – Marisol Baca »